Can Epic function as a more efficient research tool?

When pediatric urologist Vijaya Vemulakonda, MD, JD, set out to study demographic disparities in hydronephrosis treatment, she had a hard time finding enough data. To get it, she and her team created new capabilities for the electronic health record that could change the paradigm of multi-site clinical research.

Challenges to studying demographic disparity in medicine

Prenatally diagnosed with hydronephrosis, babies of ethnic minorities get surgery sooner than white ones, often within the first year. That's well documented. Dr. Vemulakonda wanted to know why. It's a trickier question than at first it seems.

"We started in 2016 with a qualitative study, interviewing parents and physicians to understand the decision-making process," Dr. Vemulakonda says. "We realized it's probably the surgeons who are really influencing those decisions. But we also found that there's no clear algorithm that determines the criteria for surgery."

Her early research suggested the role of implicit bias, but what wasn't clear was how, or at what point during the process, it came into play. What imaging studies do surgeons order, and how do they interpret the findings? How do those interpretations influence the decision whether to do surgery, or when?

"Standardizing care may reduce those disparities," says Dr. Vemulakonda. "But you need a robust pool of data to figure that out."

A robust pool of data is difficult to come by when you're dealing with a rare disease like hydronephrosis, which affects between 1 and 5% of pregnancies — just one case in a thousand of which are concerning for uteropelvic junction obstruction. But the electronic health record is a good place to start.

The drawbacks of chart review

A massive, near-ubiquitous repository of information on hundreds of aspects of care, the electronic health record has been co-opted for clinical research in hundreds of ways for years. Especially when multiple centers are involved, comprehensive chart review can reveal all sorts of hidden variables and relationships in care.

But that approach has its drawbacks. For one thing, data entry is not consistent across sites or even across providers. Different institutions use different codes. Even the codes themselves can be applied inconsistently.

"Hospital-level coding doesn’t have the nuance we're looking for," says Dr. Vemulakonda. "We care about how the surgeon interprets the images and makes decisions. It's difficult to get that kind of insight with chart review."

It's also difficult to do.

"For example, providers in urology at Children's Colorado write notes in Epic using a feature called Smart Lists," says Josiah Schissel, a clinical informaticist at Rady Children's Hospital in San Diego. "At Rady, our providers use a whole different paradigm."

That variation means researchers like Dr. Vemulakonda need informatics people like Schissel to identify the right information and technical professionals to build programs to extract it — at every site.

That demand on resources can be a major obstacle to mining quality data. It certainly was for Dr. Vemulakonda and her research partners at Rady, Texas Children's Hospital, University of Virginia Hospital and Yale New Haven Hospital. And it would make the study difficult to expand to other sites. But other sites would be essential to gathering the type and amount of data they needed.

A research-specific electronic health record module

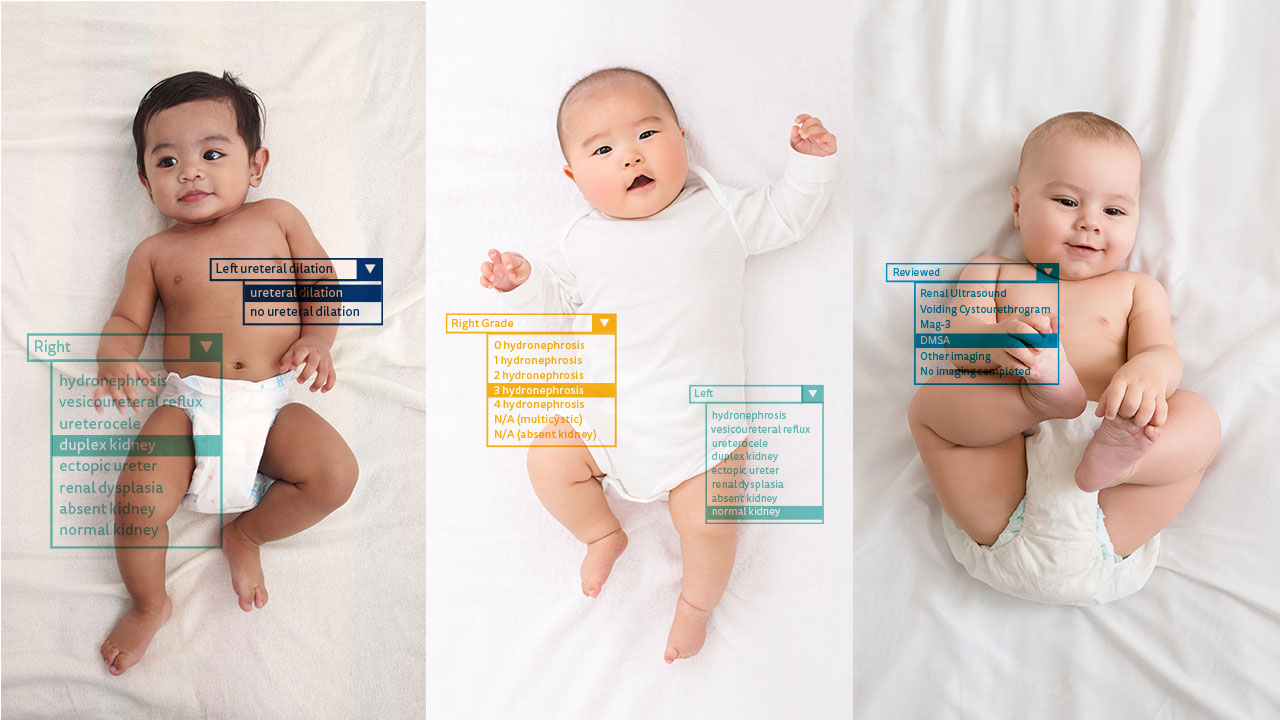

Dr. Vemulakonda and Schissel wondered if the process could be simpler. What if you could build a research-specific module right into the electronic health record? Instead of a retrospective chart review, they could gather clinically relevant data prospectively, asking surgeons to plug it in while they were already charting anyway.

As a former chair of the Pediatric Urology Steering Board for the electronic health record company Epic, Dr. Vemulakonda had some experience partnering directly with the software developer on clinical data solutions. But she also knew from experience that it could take years to see an idea like that actually implemented and rolled out.

So she and Schissel built it themselves.

"As far as we know," she says, "we're the first group to create these kind of customized templates to capture surgical data."

Integrating research into daily clinical practice

The templates they built are allowing them to follow a very small cohort of infants who get pyeloplasty over time. The goal: evaluating variations in practice, how those variations inform surgical decisions, and how variations in decisions and timing affect outcomes. The study is up and running at three sites now, with two more coming online soon.

But the beauty of the study design is that it really allows any site to participate, with minimal investment on the front end.

"We took a lot of time working with Epic to build out the data elements necessary for the research, to make it shareable with other organizations," says Schissel. "It's a lot of front-end work, but when someone on the other side of the country wants to participate, the ease of integration makes it worthwhile."

"We can just send them the data capture tool," says Dr. Vemulakonda. "It's easier to get up and running than chart review, and we've gotten rid of all these issues with data quality, because we're not using administrative data to answer clinical questions."

The efficacy of electronic health record research modules

Compared to traditional chart review in a random 10% sample, the correlation is strong between their data capture and chart review — at a fraction of the time and expense.

"We're integrating research into daily practice," she says. "It's just checking buttons."

It's an approach that could apply to a wide variety of research questions across clinical specialties, pulling together research groups from all over the country.

In the Department of Urology at Children's Colorado, clinicians and researchers are already starting to apply it: to identifying predictive factors of patient no-shows; to better understanding and leveraging practice patterns around pediatric urologic consultation; and to studying health equity barriers to accessing patient healthcare portals — just to name a few.

And ultimately, it has implications far beyond urology and even health equity, extending throughout the entire pediatric field. Already, Schissel is adapting the platform to four other research projects between Rady and Children's Colorado.

"The problem with rare disease — and that's really what we deal with in so much of pediatrics — is that no single center can generate enough data to know what best practice is," says Dr. Vemulakonda. "That's what we're trying to find out."

Featured Researchers

Vijaya Vemulakonda, MD

Pediatric urologist

Department of Pediatric Urology

Children's Hospital Colorado

Professor

Surgery-Urology

University of Colorado School of Medicine

720-777-0123

720-777-0123