Why do some children die within 30 days of a cancer diagnosis, and how can doctors help them live longer?

Technology has made an indelible mark on health research. By using new tools, scientists have sped up processes, found ways to comb through more data in minutes than might be humanly possible over a lifetime and employed artificial intelligence to make laser-accurate predictions about outcomes. But sometimes, there’s just no substitution for the old-fashioned way. That’s the approach Katie Lind, MD, a pediatric hematology/oncology fellow at Children’s Hospital Colorado, used to uncover new truths about children who die within the first month of a cancer diagnosis. Dr. Lind meticulously combed through dozens of patient charts and records in a yearslong, Holmesian search for clues.

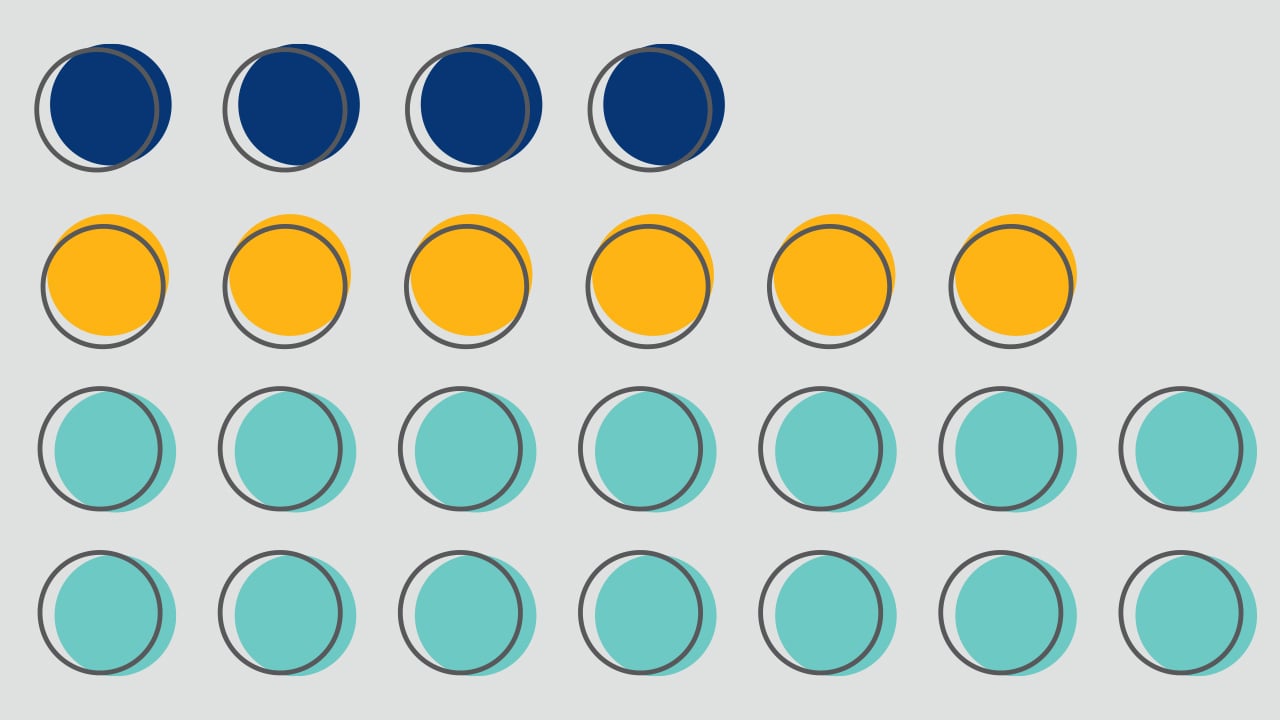

In the United States, 7.5% of childhood cancer deaths are considered early deaths (1), or deaths that occur within 30 days of diagnosis. Because these children rarely have the opportunity to enroll in clinical trials, researchers have very little data about them.

Dr. Lind’s recent retrospective study zeroed in on this population (2), building on findings brought forth through earlier research conducted by Children’s Colorado oncologist Adam Green, MD, who serves as her research mentor. In 2017, Dr. Green published a study that employed the National Cancer Institute’s massive Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results database to learn more about these patients (1). That work found associations between early death and race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status, but questions remained.

“Some of the questions that Adam was answering were: Who are these kids? Are we following them? Do we know what’s going on with them? And what he found was that we actually don’t have data on them,” Dr. Lind says. “They’re this separate group of patients who are not benefiting from all the advances that are otherwise helping kids survive cancer. There is a lot of information about these patients’ stories that just isn’t available in databases.”

Drs. Lind and Green hoped that by filling in some of the blanks and analyzing detailed information on each patient’s journey from symptom onset through diagnosis, treatment and death, they might better understand these variables and find new opportunities for intervention. They identified 45 patients who sought care at Children’s Colorado between 1995 and 2016 and who passed away within 30 days of diagnosis. Their records were compared to 44 children diagnosed with cancer who survived beyond the first month.

“I went through the charts of all of the kids, and we pulled out all of the notes from the medical team, their primary doctors, social workers and the intensive care unit,” Dr. Lind explains. “And then we got death certificates as well, trying to understand who these patients were, what they experienced and where there are opportunities for us to maybe identify them and help them to benefit from all these other advances. What can we do better in the future?”

“There is a lot of information about these patients’ stories that just isn't available in databases.”

Katie Lind, MD

The findings

Though the study didn’t uncover any significant revelations regarding social and economic factors, it did point providers to some valuable nuggets of information that may inform not only future studies, but current care.

Among the different diagnoses responsible for early death, a few stood out as the most common culprits, including leukemia. Brain and central nervous system tumors also seemed to carry significant risk for infants and young children — particularly high-grade gliomas and atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumors, or ATRT.

The study also found critical new information on the causes of death for different types of tumors, potentially keying providers into important variables to monitor. Children with brain and central nervous system tumors commonly died as a result of tumor progression, while children with leukemia were most impacted by infection. Meanwhile, those diagnosed with solid tumors had more variable causes of death.

The finding that the team expects to influence the most change though, shows that children who experienced early death had a much longer timeline between the onset of their symptoms and an initial doctor’s visit. Kids in the early death cohort had an average of 29.4 days between first symptoms and care, while the kids who survived their first 30 days after diagnosis averaged just 9.8 days. Once children in the early death cohort were seen, their timeline to specialist care and diagnosis was typically accelerated, because they were often critically ill.

“That was really novel for us because it makes us think that maybe there’s an opportunity there for intervention in the future,” Dr. Lind says. “Is there something we could do to get these kids into the system faster?”

Pathways to progress

While this study answered some important questions, it also raised new ones. Drs. Lind and Green are currently working on a new prospective study that they hope will illuminate some of the driving factors of that critical delay in initial care. The study will engage families across the country who lost children to early death from cancer. Dr. Lind hopes that by hearing directly from families, she’ll be able to identify barriers to care and ways to address them.

“In our teeny tiny sample size of 45, we really weren’t able to dig deep into that information,” she says. “Could there be a question with health insurance status? What is the primary language at home? Do you have parents who are working all the time? Do you have a primary care doctor? We just couldn’t really get enough information from the retrospective study. So that’s one of our major goals of the prospective study.”

Dr. Lind and Dr. Green hope to meet with 20 families within six months of their child’s passing to ensure details are as accurate as possible. Given the sensitive and difficult nature of the situation and conversation, the pilot study’s primary focus will be determining whether these interviews are too heavy a burden on families.

“The first aim is really to make sure that these interviews are feasible and tolerable for the families,” Dr. Green says. “There’s a good body of literature showing that conducting research with bereaved parents is very feasible, and they actually appreciate the opportunity to tell their child’s story and it can be therapeutic, but we want to make sure that in this particular setting that’s still the case.”

The duo will meet with families via Zoom and have an open-ended conversation about their experience, with a focus on psychological safety. Two weeks after that initial interview, the families will meet with a psychologist and wellness team member to ensure the process was positive and productive.

In addition to this new line of inquiry, Drs. Lind and Green are also exploring ways to engage primary care providers in educational opportunities that could lead to quicker diagnosis, particularly for dangerous brain tumors.

“We took a public health outreach campaign from the UK (3) and distilled it into a 30-minute presentation about all the main symptoms of pediatric brain tumors and when to be suspicious,” says Dr. Green, who has already educated more than 500 providers around the state through this program. “I think there’s a lot of excitement about it and hopefully we can get much larger federal funding and take it to a bigger place.”

This work may take extra effort, extra hours and extra care, but for Drs. Lind and Green, the potential to finally shed light on and prevent the loss of young lives is fuel.

“Early death has not seemed like as much of a problem as it really is. This is a population that we need to study, because otherwise we’re not going to appreciate the scope and importance of the problem,” Dr. Green says. “We need to address these problems to give them that opportunity to become long-term survivors.”

Citations

- Green, Adam L et al. “Death Within 1 Month of Diagnosis in Childhood Cancer: An Analysis of Risk Factors and Scope of the Problem.” Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology vol. 35,12 (2017): 1320-1327. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.70.3249.

- Lind, Katherine T et al. “Early death from childhood cancer: First medical record-level analysis reveals insights on diagnostic timing and cause of death.” Cancer medicine vol. 12,19 (2023): 20201-20211. doi:10.1002/cam4.6609.

- HeadSmart Be Brain Tumour Aware. “A new clinical guideline from the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health with a national awareness campaign accelerates brain tumor diagnosis in UK children — "HeadSmart: Be Brain Tumour Aware." Neuro-oncology vol. 18,3 (2016): 445-54. doi:10.1093/neuonc/nov187.

Featured researchers

Adam Green, MD

Pediatric neuro-oncologist

Center for Cancer and Blood Disorders

Children's Hospital Colorado

Associate professor

Pediatrics-Hematology/Oncology and Bone Marrow Transplantation

University of Colorado School of Medicine

Katie Lind, MD

Clinical fellow

Pediatrics-Hematology/Oncology and Bone Marrow Transplantation

University of Colorado School of Medicine

720-777-0123

720-777-0123